“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” Lenin

Don’t we all know that feeling now.

Prospect Magazine alerted me to this particularly apt quote. It is a much more evocative quote than Hemingway’s “gradually then suddenly” which is also doing the rounds with discussions of the pandemic.

Foresight and futures thinking aren’t necessarily good at spotting when exactly decades will happen in weeks. But as I discussed in my last post, they can help you prepare for and better navigate rapid change when it does happen.

In this post I describe some of the simpler techniques that can help you get started looking at post-pandemic worlds. I’ve based it on my stump presentation “How to think like a futurist.” Think of them as a set of back of the tissue, or face mask, tools that you can use regularly. More comprehensive descriptions of foresight techniques are available here and here.

Because it is long I’ll give a worked example in my next post.

The four stages of foresight

The different parts of the foresight process are often divided into four stages:

Framing – why are you doing it, what do you want to achieve, what do you need to consider and who needs to be involved?)

Perceiving – methods or practices used to identify changes and stabilities, and understanding why things are, or aren’t, happening.

Prospecting – how to make sense of the information and identify actions and strategies).

Probing – the follow-through part.

Most foresight focuses on the perceiving and prospecting stages. (And particularly on the perceiving stage.) Often too little thought is given to how the work will address critical needs of the organisation or sector, what the right questions or issues to focus on are, and how the information and insights will connect to decision makers and decisions.

Similarly, too little time can be spent on probing. This involves checking that your sense making still holds, and testing decisions to see if they are appropriate or effective (such as through research & development, pilot projects, strategic initiatives). Probing highlights that foresight isn’t a point in time activity, but a dynamic process. Not giving enough thought and attention to the framing and probing stages weaken the utility of foresight. All you end up with is a fancy report that sits on a shelf on in a digital folder.

I liken foresight to old fashioned sailing. You lack precision about where you are and where your destination is, and what’s in between. So, you frequently need to check you position, course, weather and water.

Five shapes to help explore the futures

I’m only focusing on the first three here. I’ve classified the first three stages of foresight with shapes to make it more memorable. They aren’t magical objects like the “Deathly hallows.” There are more than three and they won’t give you mastery over the future. However, they may come in handy during and after physical distancing.

Symbols illustrating key foresight steps and tools.

Framing the foresight work

A square is used for this stage since it is essential to have a clear frame to bound and direct your activity. Otherwise it’s too easy to get sucked into tidal races and maelstroms of information and forget about what you supposed to be doing. Random gathering of information isn’t going to be useful.

Are you looking at the right problem or issue? Is the purpose to develop a better understanding of your operating environment, is it to identify emerging needs or opportunities, or is it to provide options for decision makers? Do you need to be able to quantify your findings? What is your time horizon – 10 years, 20, 30, 50? – and why is that horizon important?

Framing will usually center around one or more questions, or perhaps a hypothesis. Broader questions are likely to be less useful if the intent is to directly inform strategic decisions. But questions that are too narrow risk not looking more widely at what is going on. Spending time debating what is the right frame, and the best focus question(s), is essential if foresight is going to lead to useful actions.

Examples of framing questions are:

What will the world look like in 2050? [broad and vague]

What are the key issues the New Zealand health sector may need to deal with in 2060? [more targeted]

What are the implications of more constrained globalisation for New Zealand’s agricultural sector over the next decade? [too focused, since it targets only one aspect of change affecting agriculture, and the time frame may be too short]

Framing also requires defining who’s going to be involved, how and when. For example, just pay a consultant to write a report for you, or initiate a project that runs internal and external workshops to get a wide variety of perspectives and engagement? Is a quick and simple approach or a longer and more inclusive and complicated process going to generate the insights and actions that you need?

Perceiving

Perceiving is about identifying evidence of change (or lack of change) and looking back to understand historical trends and context.

I’ve chosen a line to represent Perceiving. Actually, a broken line to symbolize filters. There is so much information to look at, and we consciously or unconsciously filter information and interpret it in different ways.

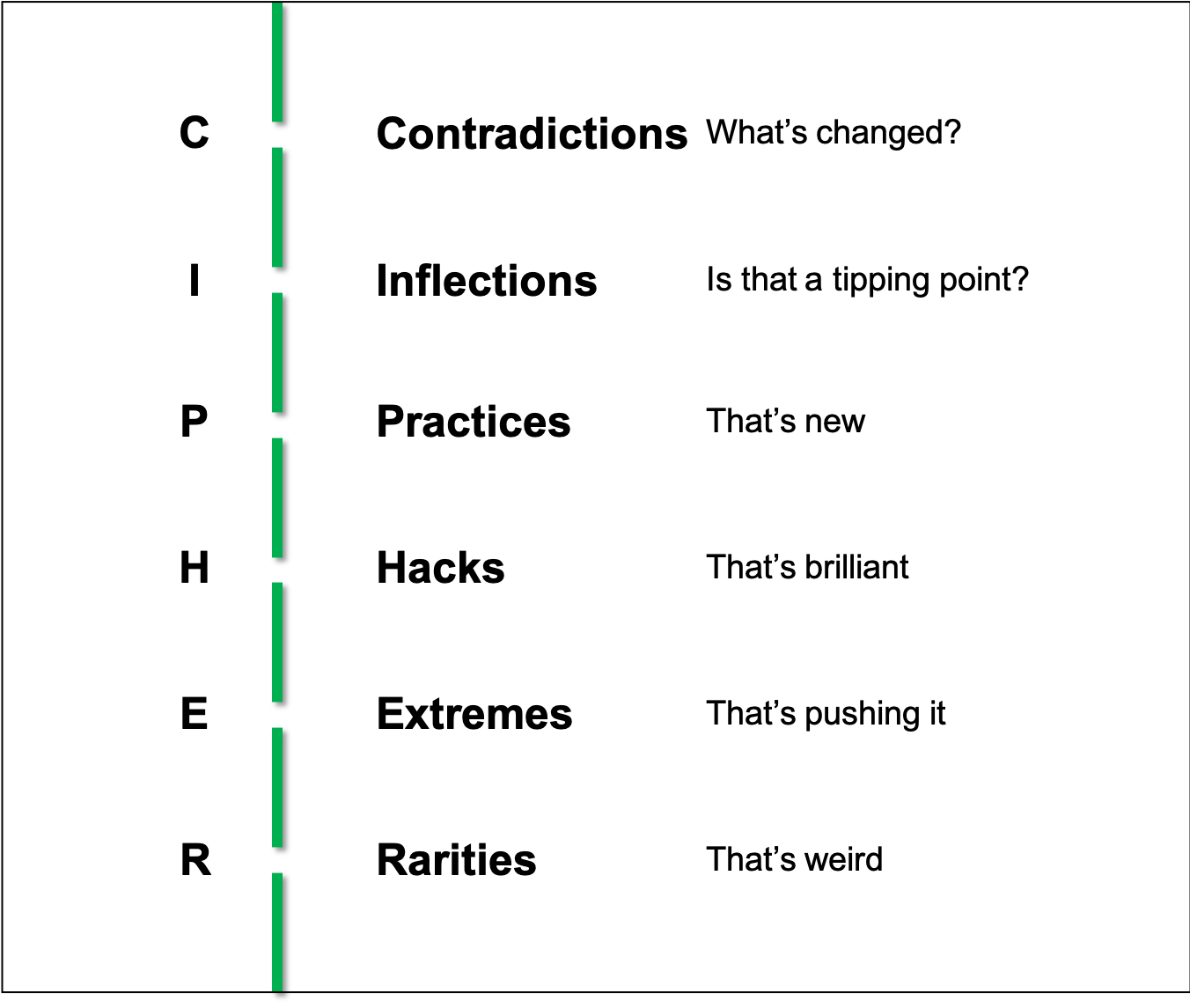

Amy Webb developed an acronym to help focus what to look for, particularly what are often called “weak signals” of change . It’s the type of stuff that makes you think “that’s interesting!”, but it also helps you look for things that you may not otherwise look out for and identify patterns. She calls it CIPHER:

Contradictions – events or actions that contradict previous behavior or trends. For example, one we are already seeing is “Big Government” back to respond to the pandemic. What are the signs this is temporary or long term?

Inflections – Such as a significant technological, social or other development. For example, the pre-pandemic large societal demonstrations for action on climate change; a shift in geopolitical influence toward Asia.

Practices – New behaviours, mindsets, ways of doing things. For example, re-establishing on-shore manufacturing of critical materials; increased surveillance for public health reasons; on-going prohibitions and enforcement of “wet markets” (or the relaxation of controls).

Hacks – Hack in the sense of unusual use of products or technologies. Or someone developing a new device or approach to solve a problem/frustration with an existing product. My favourite example is a family in the early days of the car who used one to create perhaps the first automated washing machine. In a post-pandemic world, look at how some of the hacks we are seeing from people stuck at home could lead to something bigger.

Extremes – Pushing boundaries. Like building a hospital in a week; airlines or public transport not letting you board without taking your temperature.

Rarities – Something that seems out of place but is meeting an important need. M-Pesa, the mobile phone money transfer service launched in 2007 is an example of a rarity when it originally started, and seemed weird to affluent westerners. Mining and drilling companies branching out into underground home construction in the future could be .

You don’t need to sweat what category to allocate things to. Your “hack” may be someone else’s “practice”, but the important thing is to look out for potentially significant changes.

CIPHER framework for scanning, developed by Amy Webb, Future Today Institute

Use a framework like CIPHER in addition to incorporating pre-packaged information on trends and drivers of change., so you see the bigger changes as well as the small.

Perception is also about being aware of the mental models used (by you and the audience for the project) to perceive the world. As I noted in the last blog post, Pierre Wack emphasized that scenarios are effective when they change outdated mental models . And I also wrote about how we may categorise uncertainties.

Another aspect of perceiving is being aware of the cognitive biases that influence (often unconsciously) your own and others’ thinking.

Image: John Manoogian III, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Become more aware of your own biases by taking a step back and thinking how you may be biased in your decision making (are you aware of assumptions you are making, or under- or over-discounting some information, or recent to different perspectives?). And ask others if they see bias in your thinking. Do the same with others – do they seem particularly attached to one approach or idea, is there self-interest in a specific decision, are there a variety of views, or is groupthink operating?

The best way to reduce blindness to mental models and cognitive biases is to have a diverse group involved in the perceiving.

Prospecting – making sense of changes

I’ve utilized three shapes for the prospecting stage. This is because there are at least three groups of approaches to sense making; understanding influences, exploring consequences, and developing scenarios.

Influences & Interplays

The first, symbolized by a triangle, is about understanding what is influencing and driving the system of interest. This uses Inayatullah’s “Futures triangle”, which I wrote about last week. This helps winnow down the large number of possible futures to a smaller set of plausible ones. Use it to consider how expected (or desired futures), are affected by the interplay of current trends, drivers, predetermined elements and the “weights of the past.”

But don’t be too quick to rule out very unlikely futures. You need to test your assumptions and mental models well.

Futures triangle, developed by Sohail Inayatullah

The triangle also represents Inayatullah’s “causal layered analysis” . This stimulates deeper inspection of what underpins what we see or experience (the signals or “litany”). What are the systemic factors (social, political economic) that create these, the worldview(s) that give rise to the systems, and the myths or metaphors that underpin that? This is really another way of thinking about systems, and what the points of leverage are. To change what you see involves changing the deeper layers. For example, shifting a worldview from “Small government” to “Effective governance”.

Causal layered analysis, developed by Sohail Inayatullah

Different “actors” will see or respond to different things and have different world views, as Inayatullah illustrates here.

Unpicking these perspectives and motivations is very useful for identifying plausible futures and strategies to influence &/or respond to change.

Connections & Consequences

The second area of prospecting is about understanding inter-relationships between different trends and developments, and anticipating less obvious consequences. These are represented by the circle, as a simpler summary of the “Futures Wheel”. The wheel, developed by Jerome C. Glenn, helps you explore the less obvious second and third order consequences of events or trends.

Futures wheel, developed by Jerome C. Glenn, CC BY 2.5.

It’s easy to get out to the first layer. Getting to the second and third levels often takes more mental stretching, and is best done in small groups so you can bounce off each other’s ideas.

As a quick illustration, what are consequences of greater government surveillance in communities for public health reasons?

Potential consequences of greater public health surveillance using the Futures Wheel.

You should also consider the connections and consequences of different trends or developments, rather than just having lists of individual and unconnected observations.

Scenarios - Descriptive or decisive

Lastly, scenarios. These bring all the preceding steps together to create hopefully compelling stories about plausible futures. A key change from the earlier prospecting steps is that scenarios shift you from analytical to more creative mind spaces.

Scenarios, in Wack’s useful metaphor, act as bridges between current (management) concerns and changed or changing external realities. Done well they prompt the Board and management to cross the bridge

Frequently scenarios are often presented as 2 X 2 matrices, focused on two critical uncertainties. Say degree of authoritarianism and speed of economic recovery.

Simplistic 2 X 2 scenario matrix

These, as Pierre Wack noted, are often only useful in helping you set the stage for developing scenarios that actually help decision making.

There are plenty of approaches to creating scenarios, and discussions about them can get quite academic. I’ve written a few times about scenarios (see here and here).

One way I have found quite useful in thinking about what elements should be in scenarios is the pentagon. This was reported by Mark Frauenfelder after a workshop in the US, but I’ve not seen subsequent mention or use of it.

The pentagon illustrates five key elements that scenarios should ideally have. The intention is to have at least aspects of all represented, so that readers will actively engage with them, and you can judge their “quality” by how well they cover all the elements.

Logic – scenarios with magical thinking aren’t useful for earthly decision makers. Does the scenario make sense and provide insights?

Nuance – does it convey complexity, rather than be simplistic?

Evocative – does is bring to mind a memory or image

Provocative – does it elicit a strong sentiment or reaction – excite; upset?

Stimulating – does it identify implications and actions?

Elements that a scenario should include. Source: Mark Frauenfelder

There should, in fact, be a sixth element, but that disrupts the geometric sequence and may over complicate things for beginners. I’d add “theory of change” to the mix - a clear explanation of how and why this future happened. This helps create the narrative and provides more rigor to scenario development, and evaluation of foresight. Andrew Curry writes that this is a neglected area of foresight, but is critical to provide “falsifiability.”

Creating good scenarios takes time and skill. A very logical one may not be evocative and provocative, or vice versa. They shouldn’t be last minute short stories put together without much care.

Of course, there are other methods that I’ve left out. But these should provide some starting blocks. See my next post for a better illustration of their use.

Photo by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash